You enter the polling station, get your ballot, put a tick on it and cast it into the ballot box. You just have to wait till evening when the results of national exit-polls are announced. Already in a couple of minutes after closure of polling stations you come to know who ‘has won’, and who ‘has lost’. At the same time the ballot which still recalls the warmth of your hands, together with other paper expressions of will, keeps lying in the ballot box. It is not interested in exit-polls. Not interested in what parties will make the government, and what parties be in the opposition. For the ballot it is important that it is counted, recorded in the election protocol and not lost on the way from the precinct election commission. What do we know about Ukrainian election protocols, ways and roads, and why does it all matter?

Paper and optic fibre

Each election commission must adopt its election protocol. This is, in fact, its most important ‘reporting’ document. The most important results of the day of voting are recorded there: the number of voters on the list and the number of those out of them who participated in the voting; the number of unused and spoiled ballots; the number of votes in favour of each party or candidate, etc. That is all fixed with the signatures of the commission members and the seal. Also, the protocol indicates the time when it is signed. Then the protocol is transported from the precinct to the district election commission. There it is verified and included into the Unified Information and Analytical System ‘Election’. The procedure of transferring efficient information about the results of voting is determined in Resolution of the Central Election Commission No. 1074 as of September 25, 2012.

Let us note that protocol data should in any case be recorded in the electronic system – regardless of whether the protocol contains any mistakes or not. The system records the time of data entry. In case there are mathematical divergences in the protocol, grammar or other mistakes, or it is filled out not in carefully – the district commission asks the representatives of the precinct commission to ‘specify’ such protocol. In other words, to correct the mistakes made. ‘Specification’ of the protocol shall take place in the meeting of the precinct election commission. That is, in case the DEC rejects the protocol, PEC representatives who have brought it should go back to their polling station, remove the mistakes traced, adopt the ‘specified’ protocol and bring it to the DECs for verification and acceptance. And it may go circle-wise many times until the DEC accepts the final ‘specified’ protocol.

To get clear about how large-scale the phenomenon of protocol specification is, MAG ‘CIFRA’ analyzed the number of electronic messages entered into the ‘Election’ system in the 2014 parliamentary election (in the majority component of the election system). All in all, in almost thirty thousand polling stations over thirty-five thousand electronic messages were recorded in the UIAS ‘Election’. Twenty-five thousand polling stations are marked with one message in the system, and over four thousand polling stations – with two and more electronic messages. The higher figure is eleven electronic messages from one polling station. Below is the graph of polling station distribution by the number of electronic messages.

Most electronic messages were introduced into the ‘Election’ system within four days after the day of voting. Only repeated electronic messages were introduced into the system within the last three days.

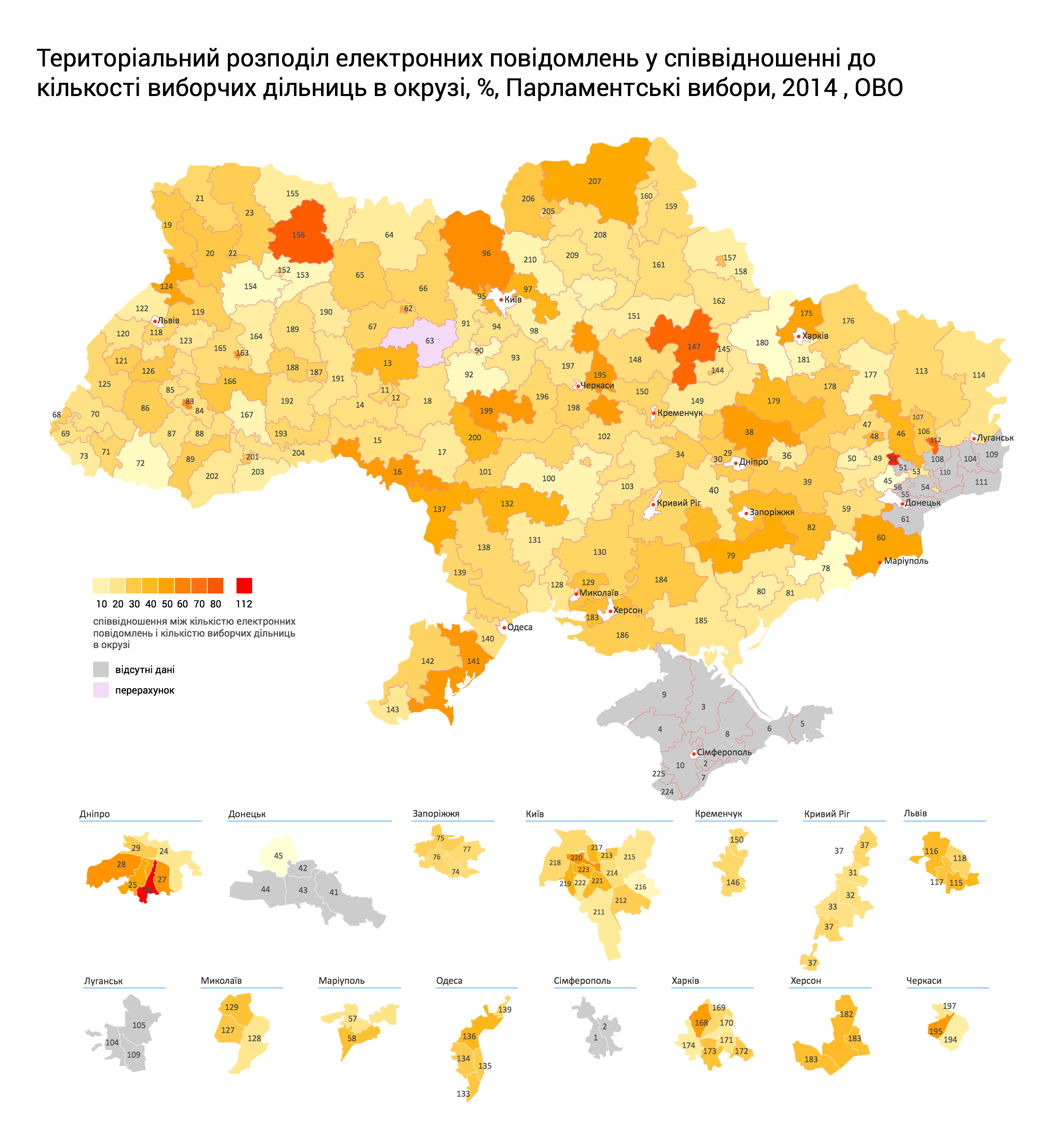

Territorial distribution of electronic messages shows that in some constituencies the number of electronic messages was 70%-80% higher than the number of polling stations in the constituency.

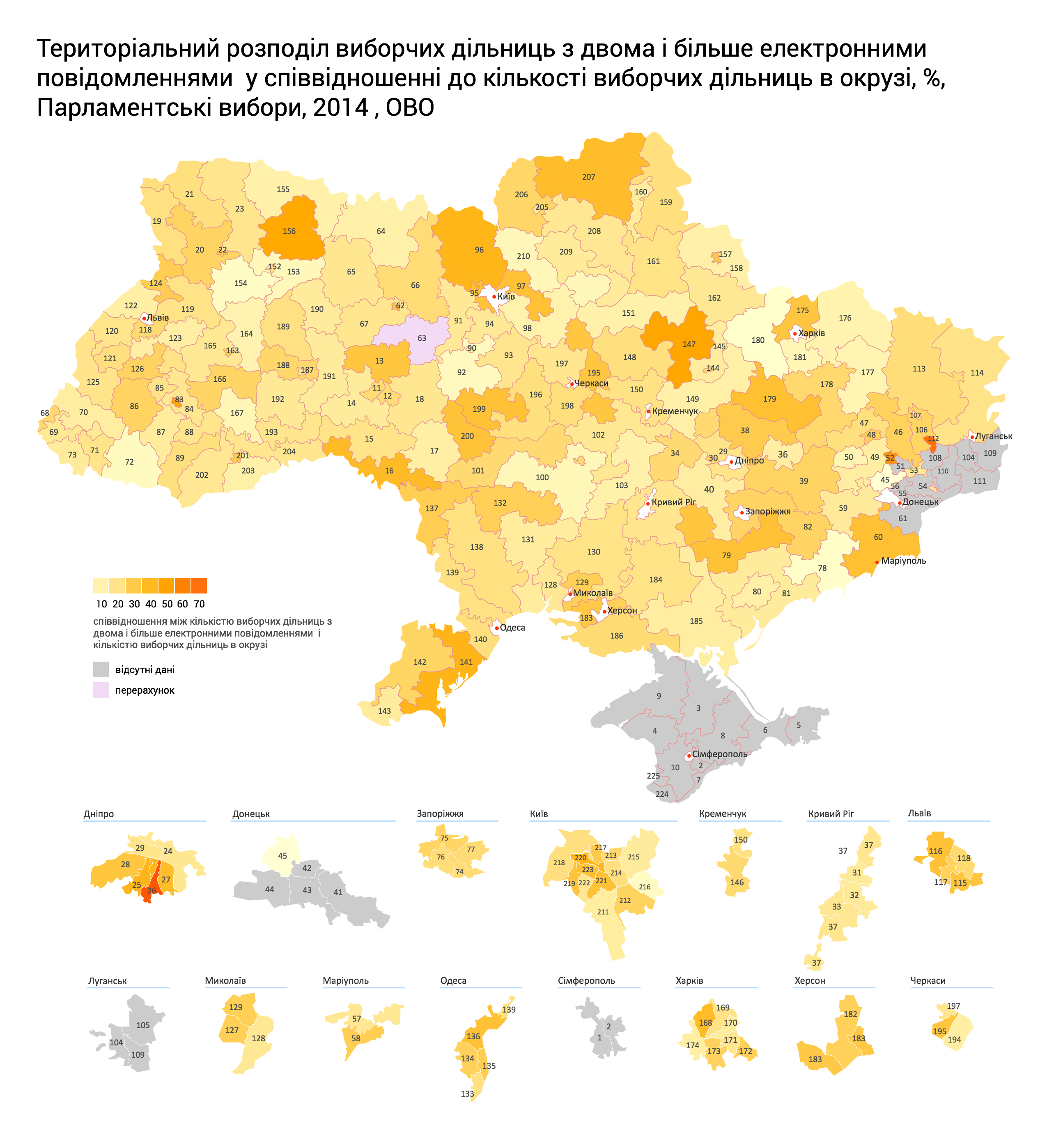

However, the previous correlation does not take into account the fact that in different polling stations of the constituency the number of electronic messages might differ considerably. For example, if the constituency has 10 electronic messages more than polling stations, these 10 messages can be divided both between 10 polling stations – one additional message per polling station, or refer to one polling station with ten messages. Therefore, further distirbution shows the correlation between the overall number of polling stations in a constituency and the number of polling stations with two and more electronic messages.

All in all, descriptive statistics allows drawing just a couple of preliminary conclusions. First, in the 2014 parliamentary election 14.4% of electronic messages more than there were polling stations were entered into the ‘Election’ system. This shows that at the stage of protocol data entry the electronic system did not ‘allow’ protocols from more than four thousand polling stations from the first attempt. In spite of the fact that there are some ‘outliers’ among the polling stations – which are the polling stations with the number of electronic messages ranging from 8 to 11, the mean for all polling stations with two or more electronic messages makes up 2.3 messages. This information by itself speaks only about the correlation and distribution. No more. But it gave rise to two questions: does the data in different electronic messages given by one and the same polling station differ? If yes, which data differs and to what extent? To answer those questions, one should know the figures in all electronic messages. Since there must be a paper protocol for each electronic message, this could respectively be done through comparing the data of initial and specified election protocols.

Archives

Original election protocols are kept in the Central State Archives of High Authorities and Management Bodies. We compiled a sample group from ten constituencies which included polling stations with the largest number of electronic messages in order to clarify why it was in those polling stations that the number of electronic messages was the largest. However, this could not be done since we found systemic, and in some constituencies – mass divergences between the number of electronic messages and the number of paper protocols from polling stations. Let us take, for example, constituency 19 in Volyn. For 14 electronic messages there was found no ‘paper’ confirmation in the archives; we also found six protocols for which there were no electronic messages available in the ‘Election’ system. Below is the number of ‘two-way’ divergences in the constituencies under study.

For some constituencies the sum of divergences exceeds 30% of the general number of polling stations. That proves that it is impossible to trace any correspondence between the content of electronic messages and paper protocols in quite a number of polling stations. In other words, the system may have three electronic messages, while there is only one protocol in the archives, and under that protocol we will not manage to trace the changes from the first up to the third electronic message. Certainly, one could try and trace such changes via UIAS ‘Election’. If they are saved there. However, that will not yield an answer to the question which has become the main one: why no complete convergence between the numbers of electornic messages and paper protocols is available for any of the ten constituencies? What could this be accounted for? At what stage of information transfer did the loss take place? Finally, who is responsible for that? These questions are more important than the divergences traced, since they refer already not to separate constituencies and polling stations, but to the system of election data transfer and accounting on the whole. One thing is when divergences in the data is traced and it can be analyzed, explained, its influence on the results of voting is determined. And quite a different thing when the divergence traced cannot be analzyed and explained. At least, using the means known and available as of the date the article is written.

‘Specification’ and Google Maps

In their reports international organizations observing the 2014 election draw attention to large-scale violations of the election protocol specification procedure. One of the main violations indicated is specification of ballots in the premises of DECs and not in the polling stations, the way the law has it. We decided to clarify to what extent such violations are systemic.

Having coordinates of the location of polling stations and district commissions, we used Google Maps and determined the best time necessary for transporting a protocol from PEC to DEC.

Then we checked the difference between the best time according to Google Maps and the time interval between entry of the first and all further electronic messages. For example, the distance between the polling station and DEC is 60 km. Google Maps show that this distance can be covered within one hour if the best itinerary is followed. If the election protocol is rejected by the DEC, the PEC representatives must get back to the polling station, specify the protocol and bring it back to the DEC. That is, they have to spend at least two hours on the way – from the DEC to the polling station and back to the DEC. The time for specification, for repeated waiting in a queue to hand in the protocol was not taken into account in our estimations. Therefore, the time difference between entry of the first and the next electronic message(s) for such polling station should be at least two hours. If the difference is smaller, there appear grounds to consider that the protocol specification procedure was not complied with. In other words, the representatives of PEC did not get back to the polling station to specify the protocol.

The results of the analysis show that out of 4,253 polling stations with two and more election protocols, 757 polling stations could be considered ‘dubious’, that is the ones which ‘coped’ with protocol specification sooner than it could physically be done. All in all, that gives grounds to claim that each fifth PEC which specified its protocol at least once did it not within its polling station.

One can draw the following conclusions on the basis of the study results. First, quantitative and territorial distirbution of electronic messages that must be made up on the basis of election protocols shows that protocol specification in the 2014 election was large-scale and ubiquitous. Second, there are sufficient grounds to consider that a large part of specifications are made with violation of election legislation, viz. – beyond the polling stations and not in the PEC meetings. Third, there exist considerable divergences between the numbers of electronic messages in UIAS ‘Election’ and paper protocols in the archives, which testify to lack of election data transfer system synchronization. Analysis made does not allow us to talk about the influence of this on the voting results, for the sake of changing them. Moreover, we cannot talk about the scale of such impact, if it occurred. However, the study gives us grounds to consider that our system of election data transfer is vulnerable to such influence.

Nazar Boyko, Roman Sverdan